In recent bird flu news, we have a report of a new H5N9 virus detected in a commercial duck farm in Merced County, California.

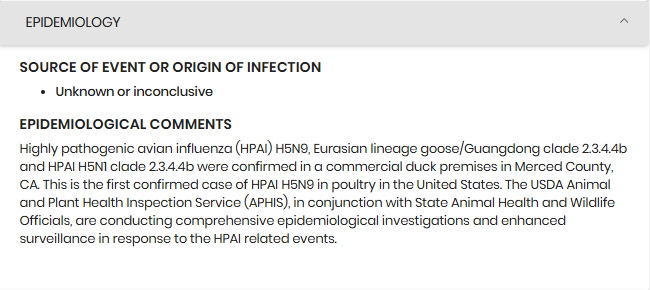

At this time we do not have many details about this outbreak or the new bird flu strain. However, the epidemiological summary on the WAHIS dashboard does provide the following information:

While I have seen some news headlines that would make it sound like this is a sign of doomsday, I will agree that it’s concerning, but it isn’t all that surprising.

This is not the first time we have seen H5 viruses pair with different “N” subtypes. Some of the more recent instances: Iceland recently reported H5N5 in several cats, and recent detections of H5N2 and H5N5 have been reported on various backyard non-poultry premises in several mid-western states, according to WOAH.

Flu viruses can mix and match and switch around genes:

These different combinations of H and N above are examples reassortant bird flu viruses, which essentially means a mix and match of different strains. The process of reassortment can happen when two different avian flu viruses infect the same host cell and swap genes around, thus creating a new viral strain or new virus. Indeed, reassortment events are what led to the emergence of the current H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses that have shown unprecedented spread. This gene swapping trick is something flu viruses are good at. This is due to the nature of influenza itself. As an RNA virus, flu has a very high mutation rate. Flu also has a segmented genome, meaning it can break its 8 genes apart and mix them around, or swap them around with some of the 8 genes from another influenza virus. It’s a bit like playing with legos.

Given the ever-changing nature of flu viruses generally, it’s not that surprising to see novel H5 subtypes pop up. This is especially true right now. H5N1 is almost everywhere, spreading through a multitude of novel bird and mammalian hosts. Indeed, it is the “high variability and rapid evolution” of bird flu viruses that is primarily concerning. We are just saturated with bird flu. Any one of the H5N1 viruses infecting dairy cattle or poultry could meet up with another flu virus and turn out something different.

What is H5N9?

To be sure, H5N9 is definitely rare. I had only heard of it once before.

H5N9 was one of several H5 viruses infecting poultry farms in France during a 2015-2016 HPAI outbreak. As in the current outbreak, H5N1 seemed to be the focus then as it is the most infamous of the H5 strains.

A 2015 study of live poultry markets in China also noted the detection of H5N9 viruses alongside other strains. That study noted that the H5N9 virus found in those poultry markets was a reassortant virus between H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2 viruses.

But this is the first time we’ve seen H5N9 in the U.S. As to the nature of the viruses identified on this California duck farm, a further note on the WAHIS report page states that both H5N1 and H5N9 were detected:

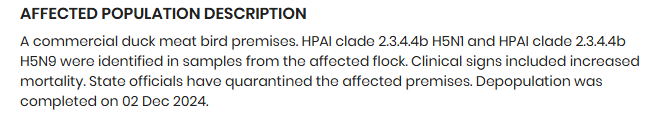

The report in WAHIS lists 118,954 birds killed/culled as a result of the outbreak. The report also indicates that the outbreak actually began in late 2024 and was confirmed in January 2025.

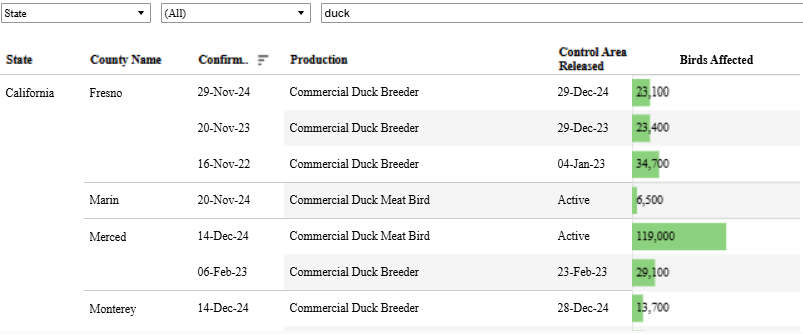

The USDA webpage showing all identified HPAI outbreaks in poultry also displays this outbreak, although not much detail other than the location being a “commercial duck breeder” farm:

So where did this H5N9 subtype come from? We don’t really know yet. My money is on a reassortment event with a low path H7N9 virus.

H7N9 has been known to circulate in poultry in the United States in the past, causing prior outbreaks. It is also known as low pathogenic in poultry, meaning that it does not cause severe disease, unlike H5N1 which is highly pathogenic in poultry and thus causes severe disease and death in poultry. So it is certainly possible that at some point H5N1 and H7N9 infected the same duck and mixed around. But when would this have happened? That’s where the genetic analysis comes in, and I hope we see that soon.

Whether this new H5 strain is an item of real concern remains to be seen. There is no word on the level of pathogenicity of this H5N9 as compared to H5N1, which was also found on this duck farm. But it does show us yet again that the more these bird flu viruses circulate, the more opportunities they have to change.

The implications of a new H5 virus in the current outbreak:

This new H5N9 virus is the only one of its kind detected in the context of the current ongoing outbreak. It is not clear if this is something we are going to see more of or if this strain didn’t get beyond the California duck farm. I will be interested to see analysis of this H5N9’s genetic sequences, which would help determine where it came from.

Something else concerning is the note about mortality in the ducks. The report does not say what type of ducks were at this farm, but waterfowl, especially ducks, typically do not develop clinical illness from H5 infection. They are considered the reservoir of avian flu viruses. So this this report about ducks dying is a bit concerning even without the novel avian flu strain.

Although it is equally concerning that ducks can be asymptomatic carriers of H5 viruses in the first place, as are other wild waterfowl, which undoubtedly has contributed to the unprecedented geographic scope of H5N1. As the virus has spread around the globe, the environment is saturated with H5N1. It continues to spread through dairy cattle herds, poultry flocks, and wild bird populations. The more this virus circulates, the more opportunities there are for reassortment with other avian flu strains. That doesn’t mean that any new viruses would necessarily be “fit” to succeed and spread. There is no mechanism by which influenza viruses “proofread” mutations, so bad ones get churned out along with good ones, and it’s a toss-up as to whether a “new” H5 virus will be better suited to spread than another. But we won’t know until that happens.

As we continue to watch nature’s grand experiment, we can only hope it doesn’t lead to the generation of a novel flu virus that has a Covid-like transmissibility but retains a more bird-flu like lethality, or somewhere in between.

Until next time.

For more bird flu updates and research study analysis, be sure to read my other articles and follow me on social media.

Leave a comment below and join the discussion, and always feel free to reach out to me!

Your prose creates lively pictures in my mind. I can imagine every {detail you describe.

I appreciate how your distinctive personality shines through in your writing. It feels like we’re engaging in a insightful conversation.

You’ve provided valuable tidbits that will certainly assist me in my work.

focmeXpgLJVmVeQuZEJgvM