Recently, there have been more reports of cats dying from H5N1 bird flu after eating contaminated pet food or otherwise exposed to the virus. Indeed, just last week, health authorities in New York City confirmed the deaths of 2 domestic cats from H5N1 after eating raw poultry products.

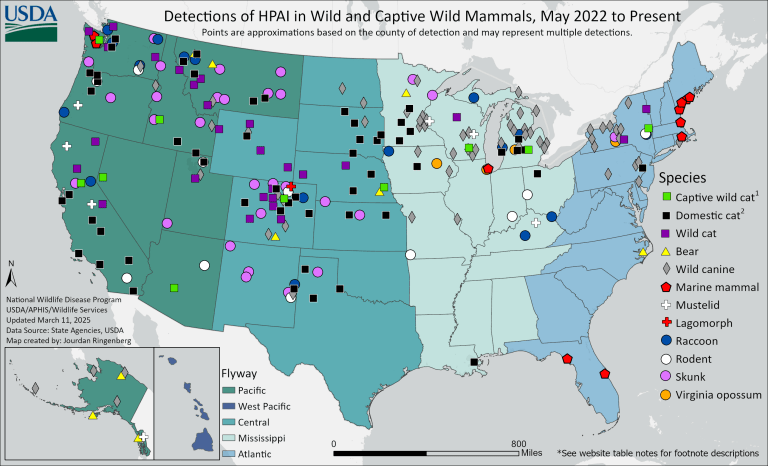

The USDA currently lists over 100 confirmed H5N1 cases in cats, but this total is almost certainly an undercount, given certain constraints like not all states report such cases, or the fact wild cats that die of the virus are not always sampled. Every so often the USDA updates its map showing the known detections bird flu in wild and domestic mammals in the country, with the most recent map showing lots of cases in domestic cats (black square) as of March 11, 2025:

The increasing H5N1 infections in domestic cats is of particular concern. Infections have been linked to the H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cattle, while others are linked to contaminated pet food, and others linked to other routes of exposure like contact with infected birds or contaminated outdoor environments. Even more concerning are cats infected with the virus with none of these exposures confirmed. What follows here is a timeline summary of recent H5N1 infections and deaths in cats, and the implications for human and animal health going forward.

Recent instances of indoor cats infected with H5N1 with no exposure to raw meat or raw milk:

In February 2025, the CDC published an interesting MMWR about an investigation of two H5N1 cases in domestic cats in Michigan. The cases were reported in May 2024. Both cats were exclusively indoor cats with no known exposure to raw pet food or milk. Further, both cats lived in households with dairy farm workers.

-

- The first cat became ill and was euthanized four days later due to symptoms. This cat lived in a house with two adults, one of which was a dairy farm worker, and two adolescents. Another cat in the same household bad symptoms, recovered, but was not tested. A third cat tested negative. The dairy worker declined H5N1 testing, but the other household members tested negative for the virus. One family member had reported a cough around the time the first cat was sick.

-

- A week later, an indoor cat from a different household began showing symptoms, and died within 24 hours. Like the first cat, this cat also lived in a household with a dairy farm worker. The dairy worker reported having eye irritation two days before the cat became sick, but he declined testing.

Ultimately, the source of these cat infections was not clear but the CDC did seem to imply there was a possibility that the cats could have been infected through contact with contaminated farm clothing or footwear worn by their owners. The study noted that the first cat did not have access to the farm worker’s work clothes, but the cat from the second household apparently would “roll in the owner’s work clothes.” Neither farm worker wore recommended PPE and therefore could have been exposed to H5N1 from dairy cattle, but as they did not get tested there is no way to know for sure.

Recent instances of cats infected with H5N1 after eating raw pet food:

Last week, New York City reported H5N1 infections in 2 domestic cats. While the initial report lacked detail, a follow-up on March 15, 2025 reported that these 2 cats, and a possible third cat, contracted the virus after eating raw pet food. A recall was issued for “Savage Cat Food” poultry packets, which the infected cats ate and subsequently developed severe symptoms (fever, loss of appetite, respiratory disease, liver disease), ultimately dying from the virus.

Not long before that, on February 28, health authorities in New Jersey reported H5N1 infection was reported in a feral cat in Hunterdon County. The cat developed severe disease and was euthanized. The report noted “other cats” on the property were ill, with “one additional indoor-outdoor cat” testing positive for H5N1. The following week, it was reported that 4 more cats tested positive, for a total of 6 sick cats from the same property. The health alerts noted that the cats had no known exposure to poultry or livestock, nor did they consume raw milk or food. However, the cats “did roam freely outdoors” and so “exposure to wild birds or other animals” was a possible source of H5N1 infection.

From December 2024 through January 2025, Los Angeles County issued several animal health alerts that were either linked to raw milk or linked to raw pet food. We previously discussed the report from December involving 2 indoor cats in L.A., who died of H5N1 after consuming raw milk, see Bird Flu suspected after 2 cats die in Los Angeles after consuming raw milk. Several days later, L.A. reported H5N1 cases in three cats from a different household, none of which had been given raw milk but were fed raw meat. Following these cases, we saw a push for stronger oversight of raw food intended for domestic pets, as discussed in Cat deaths from H5N1 positive raw pet food prompt new FDA rules.

In August and September 2024, there was an H5N1 outbreak in a zoo in Vietnam in which 47 tigers, 3 lions, and 1 panther died. It was reported that the animals “had likely fallen ill after being fed meat from chickens which had been infected.”

Of note, it has been known for some time that H5N1 had the potential to infect zoo tigers from contaminated food. For example: in December 2003, 2 tigers and 2 leopards at a zoo in Thailand died from H5N1 after being fed raw chicken obtained from a slaughterhouse. In October 2004, over 100 tigers at a zoo in Thailand died from H5N1, some after being fed chicken or pork meat, and potential transmission between tigers was noted. In early 2013, a young tiger died from H5N1 in a zoo in China after having been fed raw chicken. The following year, in April 2024, 3 tigers died of H5N1 at a different zoo in China, all of which had been fed raw chicken meat.

Beyond zoo felines, there have been several high-profile instances of domestic cats dying from H5N1 outside the United States, all cases being linked to contaminated raw food that tested positive for the virus. For example:

- In the summer of 2023, at least 30 cats in Poland died of H5N1 after consuming raw chicken meat that contained the virus. See Contaminated meat caused mysterious deaths of 30 Polish cats from avian flu. Cat owners had watched their pets suffer severe respiratory symptoms including pneumonia, and neurological symptoms and seizures. In describing the clinical picture of the cats, one case study published in September 2023 described a “systemic inflammatory response” that affected many internal organs, including the lungs and brain. Another study discussed a rare set of mutations found in all the cat viruses that was also found in samples of H5N1 positive frozen chicken meat provided by cat owners. The high similarity of the viruses pointed to a common source of infection, and the distribution of cases all across the country pointed to “an unidentified intermediate food source, e.g. poultry meat contaminated with the virus, that had accidentally entered the cats’ food chain.”

- In July 2023, at least 42 cats died in South Korea from H5N1. It was first reported that two cats at an animal shelter in South Korea tested positive for H5N1. Further reporting showed that 3 cats had died on June 24, 2024, out of 40 at the shelter. Within two days, 38 more cats died, all presumably from the bird flu virus. Several days after this outbreak was reported in July, a cat at another animal shelter tested positive for the virus. There were four confirmed cases of H5N1 from the second shelter, and all of those cats died. A study published in October detailed the investigation into these cat deaths, found that raw duck meat fed to cats in the second shelter was positive for the virus, and a recall was ordered for all pet food from the manufacturer. It was presumed but not confirmed that the cats at the first shelter were fed the same food. In August, an investigation found that one feed manufacturer had not complied with “proper sterilization and disinfection processes” in producing “balanced duck” and “balanced chicken” products sold to consumers from May to August 2023.

But beyond eating raw pet food contaminated with H5N1, there are other recent instances of H5N1 infections in domestic cats, implicating other exposure routes.

Recent instances of cats infected with H5N1 after outdoor exposure:

Before bird flu spilled over into cattle, H5N1 infections in cats were associated with exposure to infected wild birds or poultry. If you want to go far back in the way back machine, in early 2004, it was reported that 14 out of 15 cats died of H5N1 in one household in Thailand. Ultimately 3 of the cats were tested, with 2 testing positive for the virus. The owner reported that at least one of the cats had contact with dead poultry before becoming sick.

But it is the recent cat infections, those corresponding to the ongoing panzootic of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 viruses (2020-present) that is of interest today.

In December 2022, H5N1 was reported in a domestic cat in France. The cat lived with its owners next to a duck farm that had an H5N1 outbreak earlier that month. After becoming infected, the cat displayed “pronounced neurologic and respiratory symptoms” requiring euthanasia. Notably, sequencing of the cat virus showed two mutations associated with increased replication in mammals.

An interesting study out of the Netherlands sampled stray and domestic cats from October 2020 to June 2023 to determine the presence of antibodies to H5 and H1 avian flu viruses. The study found that 83/701 stray cats had evidence of prior H5 exposure, while 4/871 domestic cats had evidence of prior exposure. Interestingly, 40 domestic cats also had evidence of infection with human flu viruses. Some of the cats sampled did not die from the virus, showing cats can survive HPAI infection, likely depending on the viral load present. The study found that “seroprevalence was highest in stray cats living on dairy farms (11.0%) and in nature reserves.” The mention of dairy farms is interesting, as at the time of publication, only the U.S. has reported H5N1 in dairy cattle. As the authors note: “Cattle infected with HPAI H5 virus have not been detected in the Netherlands, but this needs further investigation.”

In January 2023, Oregon reported the deaths of 2 cats living near a backyard chicken flock. Both died from H5N1 infection. In February 2023, Nebraska reported H5N1 infections in 2 domestic cats, presumably from wild bird exposure. One cat died from the virus, and the other euthanized due to symptoms. Both cats had extensive neurological symptoms before dying, consistent with the “remarkable brain pathology” found upon exam. Nebraska reported another H5N1 case in March 2023 in a cat with an unknown source, although it was noted that “cats catch and eat wild birds.”

In April 2023, H5N1 was reported in a barn cat in Wyoming. The cat was likely was infected “from ingesting meat from wild waterfowl.” That same month, a farm in Italy reported that one cat and several dogs tested positive for the virus, but they were all asymptomatic. The farm had a poultry outbreak and had tested the animals as a precaution.

In August 2024, Colorado reported that 6 cats had tested positive for H5N1 during that year. Of those, only 1 cat had known exposure to dairy cows. It was noted that 2 of the cats were indoor-only cats and had no known exposure to H5N1, and 3 of the 6 cats were indoor/outdoor cats that were known to hunt mice or small birds.

Outside the United States, in January 2025, the first cases of H5N1 in domestic cats in India were reported, with 4 cats having died and 3 testing positive for the virus. Notably, the H5N1 viruses isolated from the cats were reassortant viruses of clade 2.3.2.1a and clade 2.3.4.4b, implicating continuing circulation of the dominant clade in India poultry (2.3.2.1a) mixing with the dominant clade globally (2.3.4.4b).

And just last week authorities in Belgium reported H5N1 in two outdoor cats, both of which were euthanized due to severe symptoms. The cats lived on a poultry farm which had an outbreak of bird flu in February. Several other cats who on the farm remained healthy. As to the route of exposure, the presumption was that the cats likely contracted the virus “by eating contaminated eggs or drinking contaminated water.”

Then we move into the Spring of 2024. In early March, just as the first H5N1 cases in cattle were discovered, there were more reports of cats dying from the virus. Only this time, there was a new source of exposure for these cats: cow milk contaminated with bird flu.

On a dairy farm in north Texas, from March 19-20, a total of 24 cats were found dead, with H5N1the cause. As discussed by the CDC in an April 2024 study, in at least one infected dairy farm, “deaths occurred in domestic cats fed raw colostrum and milk from sick cows that were in the hospital parlor.” These cats displayed severe neurologic signs, and a subsequent exam found systemic H5N1 infection. As to the cause, the study made the point that cats becoming infected with H5N1 through the consumption of infected raw milk was not something seen previously: “Direct detection of IAV in milk and the potential transmission from cattle to cats through feeding of unpasteurized milk has not been previously reported.”

So from that point on, we were in new territory.

In April 2024 we saw an uptick in H5N1 cat infections, most of them related to dairy farm exposure. New Mexico reported 3 cases of H5N1 in cats on two dairy farms, all of which died from the virus. Another case was reported in a cat in Ohio, which also lived on a dairy farm. In South Dakota, 10 cats died from H5N1, reportedly suffering respiratory and neurological symptoms. A study published on December 17, 2024 reported findings of systemic infection and neurologic disease. This study also suggested that domestic cats could act as a potential “mixing vessel” for H5N1 and another flu virus, like seasonal flu, to swap some genes around and create a novel virus, one with the capacity to better infect humans.

The implications of domestic cats becoming infected with H5N1:

The ongoing H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cattle have highlighted the risk to other animals that cohabitate on dairy farms, like farm cats. Cats that live on these farms that have ingested raw cow milk infected with H5N1 have died, and died terribly. So there is a continuing risk to these animals that are constantly exposed to dairy cattle.

The interaction between humans and pet cats can serve as an exposure point for the cats to become infected from their humans. Indeed, this is essentially what the CDC’s recent MMWR analyzing the cat infections in Michigan alluded to: each cat lived in a household with a dairy farm worker, and from the details of the investigation it sounds like there was some basis for potential exposure from the workers, although both declined H5N1 testing.

As to the risk to human health, according to the CDC, the “close interactions and proximity” of cats and humans has been cited as a concern, as such could be a route of H5N1 exposure to humans. This means that domestic cats could be another potential “intermediate host” of H5N1. Indeed, one study of the Polish cat outbreaks noted that cats have human and avian-like receptors in their respiratory tract, “and thus they could potentially serve as intermediate hosts for influenza viruses, both of avian and human origin.” This likely warrants further study, because the current clade H5N1 viruses seem to show a greater fitness for infecting mammals than prior H5N1 viruses.

To that end, the CDC has also noted that the “rapid selection of mutations” H5N1 undergoes in a mammalian host (like cats) “could result in a virus with potential for interhuman transmission, indicating a considerable public health threat.” Similarly, the authors of the recent study of H5N1 in cats in South Dakota also noted the potential for cats to act as a “mixing vessel” for H5N1 and another flu virus. That could simply be another H5N1 virus, as we saw in the recent H5N1 cat cases in India. But that could also be a mix with human seasonal flu, where a cat is infected with both H5N1 and an H3N2 or an H1N1 virus, which could swap genes around and turn out something new, perhaps with a higher chance of infecting humans. Indeed, the study of stray and domestic cats in the Netherlands noted that 40 domestic cats had evidence of prior infection with human flu viruses. All that is needed is two viruses to infect the same host at the same time.

As it stands now, the CDC maintains that the risk of H5N1 to the general public remains low. But it has published guidance on how pet owners can reduce the risks of their pets contracting the virus, including the following:

In closing, this seems like a good time to note that it wasn’t all that long ago that H5N1 was considered solely an avian virus. While spillover cases in mammals had occurred, they were rare, and they certainly did not happen as much as they happen now.

This is especially true for domestic pets like cats. Indeed, in 2004 the WHO referred to cat H5N1 infections as “an unusual event in what is an historically unprecedented situation.”

But things have changed. It has become almost commonplace to see a scattering of H5N1 cases in wild mammals and, more recently, domesticated mammals like dairy cattle or cats. When did it become so normal to talk about bird flu in animals like cows and cats?

The goal posts have been moved, we just don’t know how far yet.

Until next time.

For more bird flu updates and research study analysis, be sure to read my other articles and follow me on social media.

Leave a comment below and join the discussion, and always feel free to reach out to me!