The H5N1 strain of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, what we typically refer to as bird flu, has infected an unprecedented number of wild birds and mammals around the world. This global pandemic in animals, a “panzootic,” is unprecedented because never before have so many different species been infected with this virus. On another note, I have also never seen the word unprecedented used so many times in research studies as it has been in those published in the last four years or so, which is not without cause, but I did find it interesting.

The clade of H5N1 currently circulating the globe, clade 2.3.4.4b, has infected and killed more species of wild birds than an H5N1 virus has in the past. It’s also set a record for spillovers into an ever increasing number of mammalian species.

H5N1 Infections in Mammals:

For example, consider the red fox: H5N1 has caused the deaths of wild red foxes around the world, including the United States, Germany, Finland, and Denmark. Studies of the same have revealed evidence of mutations associated with increased viral adaptation to mammals, as well as severe neurological symptoms associated with viral spread to the brain and central nervous system.

Other mammals have suffered similar fates, way more than can be covered in one article. H5N1 has infected and killed cats in Poland and France, black bears in Canada, and seals and sea lions in Chile and Peru. Scientific studies of these events have found that the viral strains infecting these animals contain mutations that are associated with mammalian adaptation. This clade of H5N1 first began infecting more species of wilds birds than it had before, and killing more species of birds than ever before. It continues to infect a growing number of mammalian species. In some animal groups, H5N1 has caused massive die-offs.

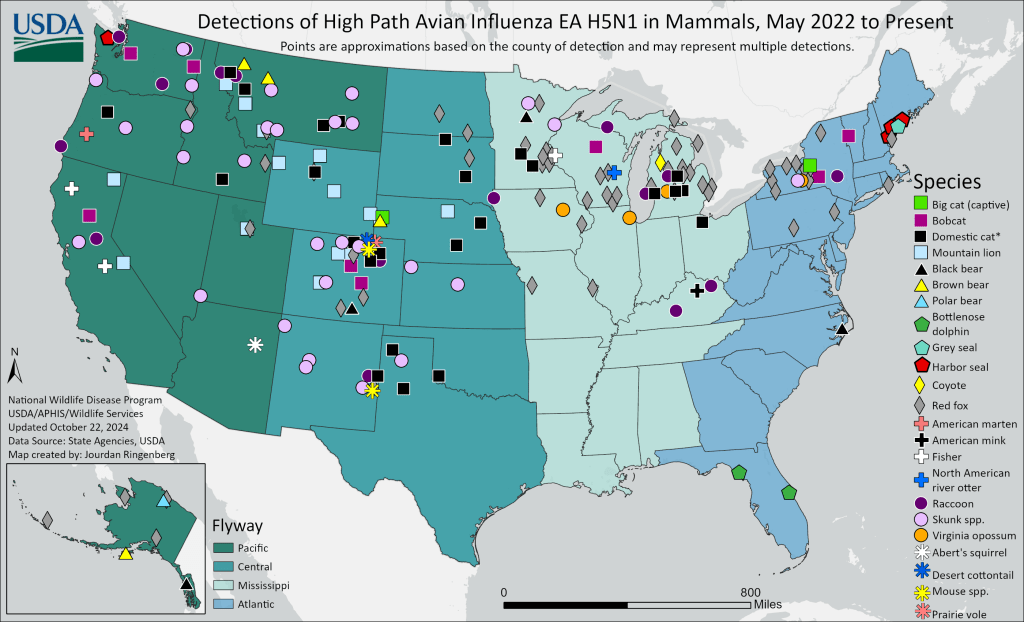

In the United States, it has infected more than two dozen different species of mammals. The USDA even has a great map on the subject that it updates periodically, as seen below. The most recent additions to the USDA’s map were bottlenose dolphins in Florida, and a red fox in Alaska, all confirmed positive in October 2024.

Current map of known mammalian infections with H5N1 in the United States as updated by USDA APHIS.

The New H5N1:

So this virus, bird flu, is moving beyond birds. How? What changed? How has the virus changed so that it can cross this barrier so readily? Why has it been able to infect and kill so many new species in such a short time? These are some of the many questions the research studies are attempting to answer.

This new H5N1, sometimes referred to as “contemporary” H5N1, is a far cry from vintage 1997 H5N1. In many ways this is a good thing, given the mortality rate of that virus. But right now H5N1 seems to exhibit an increased fitness for infecting and killing global wildlife. This includes wild birds and wild mammals, causing significant mortality rates in multiple different species within the last few years. The high death rates in wildlife aside, just the fact that H5N1 has an increased fitness for crossing the species barrier is concerning, and it is not yet known why this clade of H5N1 is more suited to do so.

What we do know is that the more H5N1 continues to infect mammals, especially different species of mammals, the more chances the virus has to mutate into something more adaptable to mammals, including humans. This is without even infecting humans directly, which is itself another problem. But even just the spillovers into mammalian populations are alarming, because we are mammals after all, and we are more connected to the animal kingdom than we like to believe.

Human H5N1 Case in Chile:

Take the human case from Chile back in March of 2023. A 53 year old man living in a coastal area of northern Chile tested positive for H5N1. He was hospitalized and was quite ill. That same month hundreds of sea lions had also died from the virus. An investigation found that the man lived near a beach where sea lions and wild birds had recently died of H5N1, and so it was thought his exposure came from the environment. But how exactly? They still do not know for sure. The good news is the man survived. He remained under intensive hospital care for months, until he was discharged in late June. Samples of the virus from this human case as well as from sea lions and shorebirds in the area were studied. The human virus and the virus from one of the sea lions each contained the same rare mutation known to be a marker of mammalian adaptation.

Mass Mortality Events in Sea Mammals:

Other mass die-offs in mammals have occurred, all from H5N1 infections. These are just some that have occurred during the last few years as H5N1 has swept around the world:

- In early 2022, hundreds of seals were found dead or dying off the coast of New England.

- In early February 2023, 55,000 wild birds and over 500 sea lions died in protected areas in Peru.

- In October 2023, more than 400 sea lions died on the beaches of Uruguay.

- That same month, over a thousand baby elephant seals died in Argentina.

These are “mass mortality events” (or “MMEs”), which is what they sound like: an event in which an incredibly large number of animals die. In this case, the cause of death is infection with H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b. The loss of wildlife from these events is enormous, and it is an ongoing concern for scientists and conservationists. These MMEs are a huge loss of life for vulnerable animal populations. They are also a signal of viral change, in H5N1’s ability to infect a large group of mammals at one time, causing disease and death.

Ecological Impact of Mass Mortality from H5N1:

This clade of H5N1 is everywhere except Australia, as it recently reached the islands off the coast of Antarctica leading to the deaths of elephant seals. It has also devastated wild bird populations around the world, as many species of birds actually have no prior experience with bird flu. This H5N1 has further defied expectations by failing to follow the seasonal pattern typically associated with wild bird migrations, and instead persisted for several years through different bird populations. This is worrying in terms of ecology and conservation, and it should also be at least concerning, if not worrying, from a public health standpoint.

As to the wild birds that have died, what do they eat? What happens when that population substantially decreases, and they are no longer eating the bug or pest that was its diet? What other animals rely on those birds as a food source, and what happens if that food source is suddenly a lot harder to find? What will those animals eat instead? And if those animals turn elsewhere, what are the downstream ecological impacts of those changes? You can see there is a rabbit hole of questions here.

And then there are the sea mammals, like sea lions and seals. What do they eat? What are the effects of losing so many animals in a specific population? What is the impact of loss of breeding? And, as in the case of the loss of over a thousand baby elephant seals, what happens to that animal population when almost an entire generation is gone in an instant?

These are questions for wildlife experts and for the people who study those wildlife populations, all of whom are likely very very concerned. But they concern me too. Unfortunately I don’t know the answers to these questions.

Spillover Risk at the Human-Animal Interface:

The unprecedented spillovers of H5N1 into so many different mammals has highlighted just how connected the animal kingdom is. The mass mortality events in sea mammals typically coincided with wild bird die offs in the same area. Those wild bird die offs occurred where they occurred based on the migration patterns of the particular bird species. The presence of sea mammals in the same area was the result of that species’ behavior, breeding habits, hunting habits, and general ecology. Its a jumble of factors bringing these different animal populations together under just the right circumstances, from the virus’ perspective at least.

But humans are not insulated from the interconnectedness of the animal kingdom. We are an integral part of it. Spillover of H5N1 from mammals into humans has, for the first time, been confirmed at the unexpected human-animal interface of dairy cattle farms.

As more studies are done on these events, the scientific community will be paying close attention to factors that may suggest an increased risk to human health. This would include viral samples showing mammalian adaptation markers, mutations that are associated with increased virulence in mammals, and mutations known to relate to increased receptor binding or transmission in mammalian species.

As the authorities continue to say, the risk to human health is not high right now. But the future holds no guarantees. This H5N1 has already defied the scientific community’s assumptions about avian influenza on more than one occasion. Every day more studies are published on key aspects of this ongoing “panzootic” (pandemic in animals) and we continue to learn more.

We also continue to ask more questions. At least I do. How has this virus been able to persist in wild bird populations for years? How has it been able to kill thousands of sea mammals in numerous mass mortality events? Will more land based mammals get infected and die? At what point does the concern for human health increase?

Stay tuned.

For more bird flu updates and research study analysis, be sure to read my other articles and follow me on social media.

Leave a comment below and join the discussion, and always feel free to reach out to me!

Your post is a game-changer; it challenged my viewpoint.

Thank you!! I’m so glad it’s making waves!

Pingback: As H5N1 continues to cause mortality in wild birds, are we closer to a flu pandemic? - Bird Flu Studies

You have provided a fresh take on a typically discussed topic; I appreciate the unique perspective.

I have learnt some valuable advice from reading this.