Cases of H5N1 in humans have been on the rise as more and more dairy cattle herds and poultry farms are infected with the bird flu virus.

On 12/4/24 the CDC added an additional bird flu case to its official list of H5N1 human cases in the U.S. The total official count of human cases is now at 58. The official tally is very likely, if not certainly, an undercount.

Recent human H5N1 cases not (yet) included in the CDC’s official count:

2 new human cases in Arizona:

On 12/6/2024, Arizona reported two human H5N1 cases, the first to be reported in the state. In a press release, the state department of health services noted that both people were exposed to infected poultry while working at a commercial poultry farm. Both poultry workers reported “mild symptoms, received treatment and recovered.” The two cases are from Pinal County, which is in south-central Arizona:

Of note, it was only last month that Arizona reported its first detection of H5N1 in poultry in several years at a commercial poultry farm, also in Pinal County. The news release does not state whether this poultry farm is the same as the one where these two people worked. These 2 recent human H5N1 cases in Arizona are not currently reflected in the CDC’s official count.

1 new human case in California:

Additionally, on 12/6/2024 California reported another potential H5N1 human case. In a local public health update, a possible bird flu case was reported in a child in Marin County, California. The LA Times reported that local public health officials have been investigating “since last week.” The local health update notes that the CDPH is currently working with the CDC to “confirm if it is a case” and then determine the source of exposure/infection.

As the update above mentions, and as previously discussed on this blog, there was a reported bird flu case in a child reported in November in Alameda County, California, the source of infection never identified. This would be the second reported H5N1 case in a child in that state. This recent H5N1 human case is not (yet) included in the CDC’s official case count.

The official count of human H5N1 cases is low:

This official count of human bird flu cases in the U.S. is almost certainly an underestimation. The official tally reflects the results of targeted surveillance and testing where H5N1 has been found in livestock, and testing must be consented to. Furthermore, in addition to the newly identified and/or suspected cases noted above, there have been several instances over the past few months indicating that some presumed positive cases, or even positive cases later discovered, are not accounted for in the CDC’s official list:

-

- The CDC count does not include the 8 presumably mild or asymptomatic cases of H5N1 found by serological testing. This testing found that 7% of exposed dairy farm workers had serologic evidence of H5N1 infection, and that’s only the workers who were involved in this study.

-

- The CDC count does not include the second, strongly suspected, human case in Missouri, who was a close contact of the first human case. Serology tests of 5 healthcare workers who cared for the first case were all negative, but one of the three serology testing methods came back positive for the close contact of the first case. The route of infection may have been a common source for both people and not transmission by the first case, but we still don’t know how either person was exposed to H5N1.

-

- The CDC count does not include cases that were confirmed by state laboratories but not by the CDC. These are referred to in a curious little footnote at the bottom of the CDC chart: “Additional cases meeting the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) probable case definition have been reported by states: 1 case with dairy cow exposure (CA), 3 cases with poultry exposure (WA). Confirmatory testing at CDC for these cases was negative.”

-

- It is also worth mentioning that throughout the H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cattle, there have been anecdotal reports of dairy farm workers being sick with flu-like illnesses, some of them missing work, but were never tested. So we really don’t know how widespread mild human bird flu infections have been.

Recent human H5N1 cases that are included in the CDC’s official count:

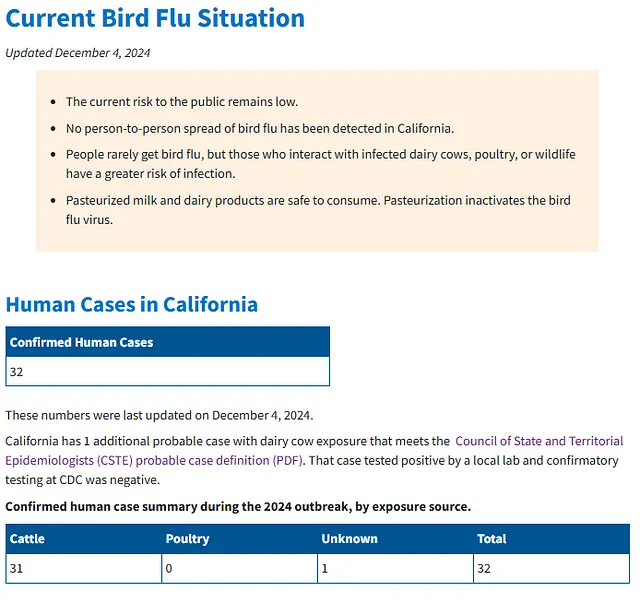

The last official total was 57 human cases as of 12/2/2024. The 12/4 update incorporated one additional case reported in California, as the CDC chart pictured above shows it increased California’s total H5N1 human cases from 31 to 32. Indeed, on 12/4/2024, the California Department of Health updated its official count on its website, increasing confirmed cases to 32 human H5N1 infections. No details were provided on this new human case.

Only two days before that, the CDPH had added 2 new human cases to the state’s total, bringing it up to 31. These 2 human cases were then added into the CDC’s official list, and some details on these cases were provided on the CDC’s FluView database. Per FluView, those 2 cases were both dairy farm workers with exposure to sick cattle:

It was only two months ago that California was investigating the first “possible” case of bird flu. Fast forward to today, and there are now 32 human cases in that state, all but 1 of which was linked with exposure to sick cows. The 1 exception was the case identified on 11/19/24, in which a child from Alameda County tested positive for H5N1. The child experienced “mild respiratory symptoms” and was not hospitalized. The child had no known contact with an infected animal. There has not been any further information as to how this child was exposed to or infected with this bird flu virus.

So things are clearly picking up on the bird flu front.

Human Bird Flu Cases are Increasing:

The acceleration of human bird flu cases in California, the state with the most dairy herds infected, is alarmingly consistent with the acceleration of human cases in the United States.

April 2022: 1 case

Prior to this year, the only human case of H5N1 in the U.S. was from April 2022 on a commercial poultry farm in Colorado. The CDC reported on April 28, 2022, that a person involved in the depopulation of poultry infected with H5N1 had tested positive for the virus. This was big news at the time, as it was the first human case of H5N1 in the U.S. The case was very mild, as the person only reported experiencing fatigue. According to the WHO statement on the case, the man developed fatigue on April 20, 2022 during his participation in slaughtering infected poultry from April 18 – April 22. A respiratory sample was obtained on April 20 and testing was completed by the state laboratory on April 25 which showed positive influenza A infection. The CDC confirmed H5 virus infection on April 27, with the subtype N1 subsequently confirmed.

During this time, H5N1 infections had been confirmed in poultry flocks in at least 29 states, as well as wild birds in at least 34 states. Interestingly, there was some uncertainty as to whether this was a proper case of bird flu or the result of “contamination” of the nasal passages without actual infection, but given the positive test result the CDC treated it as a true H5N1 human infection and the person was provided with oseltamivir. This Colorado case was an outlier as there were no other cases reported, even amongst other people involved in the same culling operation on the same farm. In total, 9 contacts of the positive case were tested and monitored, all of whom tested negative.

Of note, in the press release announcing this human case in 2022, the CDC stated: “This one H5-positive human case does not change the human health risk assessment. CDC will continue to watch this situation closely for signs that the risk to human health has changed. Signals that could raise the public health risk might include multiple reports of H5N1 virus infections in people from exposure to birds, or identification of spread from one infected person to a close contact. CDC also is monitoring H5N1 viruses for genetic changes that have been associated with adaptation to mammals, which could indicate the virus is adapting to spread more readily from birds to people.”

April 2024 – Present: 58+ cases

Less than two years later, we are now unofficially at 60+ human cases of H5N1. That’s unheard of for the United States. At least it was, until dairy cattle became infected.

The initial dairy cattle infections in Texas led to the efficient transport of H5N1 to more than 700 dairy herd locations in the US, and the number of infected herds continues to rise. The fact that H5N1 could infect cattle so readily took the scientific community by surprise, as did the way this virus was manifesting in these cows, and thus the transmission features were poorly understood in those early months.

The dairy cattle outbreaks have facilitated dozens of spillover infections of the virus into farm workers at that human-animal interface. The apparent ease with which this bird flu virus infects humans is alarming and reflects one of many changes this clade of H5N1 has demonstrated. Indeed, these types of changes in the epidemiology and ecology of H5N1 have been noted by scientists for several years. But now there is a very clear manifestation of those changes. There are also additional H5N1 outbreaks in poultry, some of which have led to additional human cases from direct poultry exposure.

The CDC officially lists 58 human cases of H5N1, all occurring in 2024. The first case was identified in April 2024, in a dairy farmworker in Texas. Since then there have been (at least):

-

- 21 human H5N1 cases associated with exposure to infected poultry

-

- 35 human H5N1 cases associated with exposure to infected dairy cattle

-

- 2 human H5N1 cases with “unknown” exposure

H5N1 infecting and adapting to mammals, including humans:

So is there evidence that the current clade of H5N1 is adapting to mammals, and possibly to humans? Sequencing of some viruses from the 2024 dairy cattle outbreaks and related human H5N1 cases have found some genetic changes that are worth noting.

-

- The virus from the first human case identified in 2024, the Texas dairy farm worker, carried two mutations associated with adaptation to mammals. The PB2 E627K mutation is a known marker for increased replication in mammals and more severe disease. The PA K142E mutation is associated with increased virulence in mammals when combined with PB2 E627K.

-

- Sequences from subsequent human cases showed adaptations associated with reduced susceptibility of antiviral drugs. For example, the PA-I38M mutation, associated with reduced susceptibility to baloxavir, was found in a viral sample from 1 human case in California. The NA-S277N mutation, which is associated with reduced susceptibility to oseltamivir, was found in H5N1 virus samples from 3 human cases in Washington State.

Further, some bird flu studies have found that viruses sampled from the dairy cattle outbreaks and associated human cases are transmissible between ferrets in the laboratory. This is one of the key factors for public health authorities considering the pandemic risk of novel flu viruses. For example:

-

- A study published in July 2024 using an H5N1 virus isolated from the milk of an infected dairy cow in New Mexico, found that this virus showed dual receptor binding qualities, in which the virus bound to both avian and human receptors. This study also found evidence of a very low level of transmission to 1/4 contact ferrets, but not resulting in detectable infection.

-

- A study using the H5N1 virus from the first human case in Texas, published in October 2024, found that this H5N1 virus transmitted by respiratory droplets between ferrets, and replicated in human lung cells in the lab.

-

- In a CDC study published in November 2024, using the same Texas human H5N1 virus, found that this virus spread to 3/3 direct contact ferrets, and spread by respiratory droplets to 4/6 airborne contact ferrets. The CDC itself seemed somewhat surprised by these results, stating: “The observed capacity of avian influenza A(H5) virus to transmit via respiratory droplets in ferrets has not been frequently reported in the past.” I’ll say.

-

- Finally, a very recent study published on December 5, 2024, also using the H5N1 virus from the human case in Texas, found that by a single mutation in the HA gene, Q226L, this virus switched its receptor binding preference from avian a-3 receptors to human a-6 receptors in the lab.

Taking all this together, there does seem to be some bird flu virus evolution going on here. If nothing else, for an H5N1 virus to be able to bind to human a-6 receptors is very noteworthy, and also concerning. This switch in receptor binding is one of the key considerations in weighing the risk to public health, as a virus cannot gain traction and spread amongst humans until it can efficiently infect and transmit between humans, and it can’t do that without first binding to the human-style receptors and infecting the human cells. Such is not the typical “norm” for H5N1.

And yet we now have several studies on recent H5N1 viruses that exhibit the capacity to bind to human a-6 receptors. Although, to be sure, what happens in the laboratory does not dictate what happens in nature. Nature is her own mistress. But as this bird flu virus continues to make its way through dairy cattle across the United States, it will continue to change. It will also continue to infect humans that work closely with infected animals. It may also infect wild birds that come into contact with infected cattle herds, or infect poultry or other livestock on the same farm. Indeed, as we have already seen, there are multiple ways that H5N1 can infect different hosts.

As the virus continues to infect new hosts, it will continue to adapt. Where that leads is far from clear, but we could at some point find ourselves facing a bird flu virus that is more suitable for not only infecting humans but transmitting between them.

Until next time.

For more bird flu updates and research study analysis, be sure to read my other articles and follow me on social media.

Leave a comment below and join the discussion, and always feel free to reach out to me!

Your blog entry has encouraged me to make a move. I’m excited to test your suggestions!

Your prose has a vibrant quality that creates clear pictures in my mind. I can immediately picture every aspect you describe.

Pingback: No human transmission from child infected with H5N1 bird flu - Bird Flu Studies

Pingback: Mexico Reports First Human H5N1 Case - Bird Flu Studies