A person from the state of Washington has died of H5N5, a strain of bird flu.

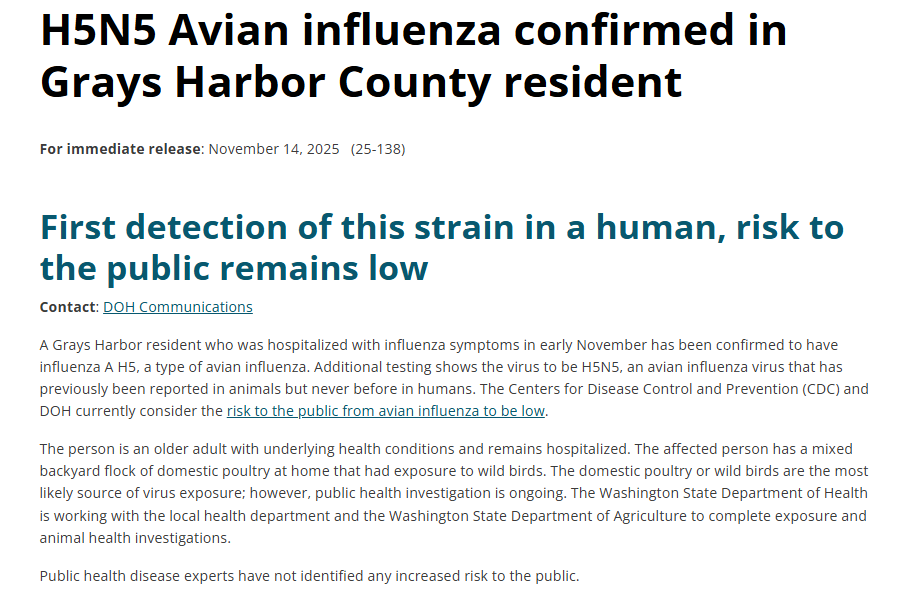

The state department of health previously reported a novel H5N5 infection in a resident on November 13, 2025. We still don’t know much about this person other than they were an “older adult” with “underlying health conditions conditions” who was hospitalized “with influenza symptoms” earlier this month.

On November 21, 2025, the health department reported that the patient unfortunately died. Details are lacking on this case. We don’t know much about the progression of disease or clinical picture while this person was hospitalized.

First Ever H5N5 Human Case

This is the first time H5N5 has infected a person, at least as far as we know. Not only is it the first known human case with H5N5, it was a severe case requiring hospital care and resulting in death.

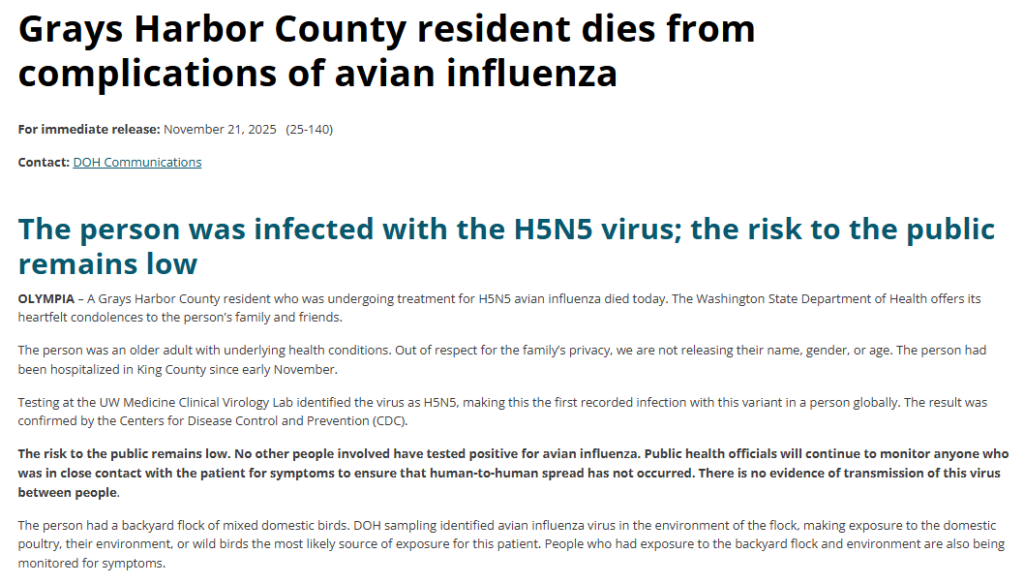

As for the mode of transmission, this person apparently had “a mixed backyard flock” at their home. But what type of mixed flock? Are we talking chickens and turkeys, or ducks too? This backyard flock is believed to have had “exposure to wild birds.” So at this point the presumption is that wild migratory birds carrying the H5N5 virus somehow infected this person’s own backyard flock, which then somehow passed on the infection.

Having a backyard flock is already a known risk factor for avian influenza exposure. Indeed, we saw this with the first death from H5N1 in the United States, in a Louisiana man with a backyard poultry flock. (See The First Fatal Case of H5N1 Bird Flu in the U.S.). But what kind of flock did the Washington State resident have? What kind of wild birds did that flock interact with? More importantly, what interactions did this person have with their own flock that led to them getting severely ill?

The H5N5 Virus

It’s important to note that H5N5 is a different bird flu virus than the H5N1 virus that has been center stage for several years.

From genetic sequencing we know that the H5N5 virus was not the result of the H5N1 virus mutating into something new. Instead, the H5N5 virus that infected the person in Washington is closely related to H5N5 viruses already known to circulate in wild birds. (For further reading on H5N5 I really liked this study: Multiple transatlantic incursions of highly pathogenic avian influenza clade 2.3.4.4b A(H5N5) virus into North America and spillover to mammals, Cell Reports (July 2024)).

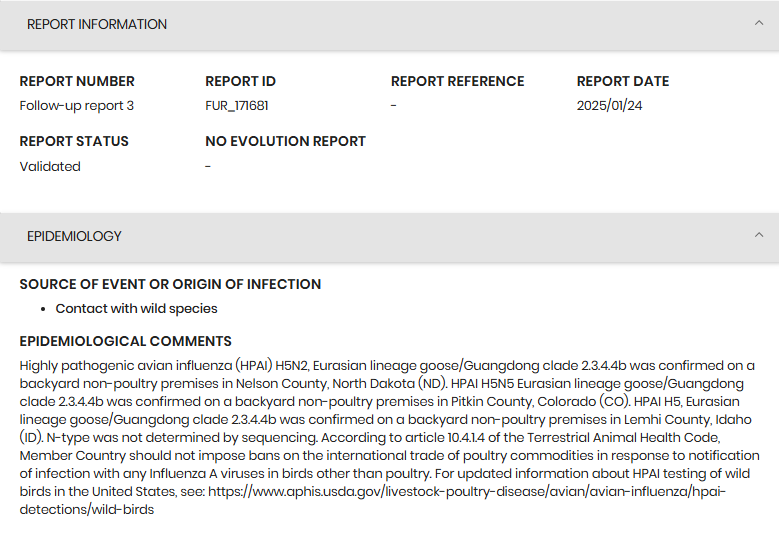

What strikes me is why now? H5N5 has been documented in migratory birds but this is the first spillover into a human. Even reports in backyard flocks were scarce, although they did happen. Indeed, this past January various H5 virus strains were found in domestic flocks in the United States, including H5N5. As noted on the legendary WAHIS dashboard, H5N5 bird flu was noted in a Colorado flock:

But is there more H5N5 virus circulating now? If so, could this suggest this H5N5 virus is somehow more fit to circulate widely in wild birds, then travel down the pacific flyaway where those birds have interactions with domestic poultry in a Washington backyard? Or have H5N5 viruses been already doing that, but only now caused a human case?

No Additional Human H5N5 Cases Found

As the press release above notes, the risk of further infections as well as spread between humans is considered low. But there were some interesting tidbits from the press release, such as:

“The risk to the public remains low. No other people involved have tested positive for avian influenza. . . . ” – No other people “involved”? Involved in what? That just seems vague to me. If that refers to involvement in caring for the backyard flock I would like to see more details as to the nature of that involvement and whether the patient had more extensive contact with those birds.

“DOH sampling identified avian influenza virus in the environment of the flock, making exposure to the domestic poultry, their environment, or wild birds the most likely source of exposure for this patient. People who had exposure to the backyard flock and environment are also being monitored for symptoms.” – Whenever I see mention of bird flu “in the environment” my sense of unease grows a little, as that is much more broad than simply having exposure to a sick flock. Moreover, this says that people “who had exposure” to either the flock or the environment are being monitored. How many people is that? What were they doing? What type of environment are we talking about here?

So many questions. Hopefully we get answers to some of them. But as prior cases have shown us, we won’t always know the full story of how and why this person was infected. Without the full picture, it makes preparedness that much more difficult. Hopefully we learn as much as we can from this H5N5 human case, which marks yet another milestone in the journey of avian influenza.

Until next time.

For more bird flu updates and research study analysis, be sure to read my other articles and follow me on social media.

Leave a comment below and join the discussion, and always feel free to reach out to me!